Presentation, analysis, cross-study of keynote papers prepared by different waste management actors, including civil society, helped the 41 participants in elaborating shared viewpoints and outcomes regarding the prior topics to be considered.

Prevent and anticipate through transparency and participation

Presentation, analysis, cross-study of keynote papers prepared by different waste management actors, including civil society, helped the 41 participants in elaborating shared viewpoints and outcomes regarding the prior topics to be considered.

EURAD-2 is a European project 🇪🇺 dedicated to a safe radioactive waste management ☢️🚮 which follows EURAD-1 programme started in 2019 and ended in may 2024. Along waste management organisations, technical support organisations or research entities, Nuclear Transparency Watch 🔎 was included as a “linked third-party” to coordinate the participation of civil society members in some of the work packages. The results of EURAD-1 from the civil society point of view were shared on NTW’s website here: https://www.nuclear-transparency-watch.eu/activities/synthesis-of-the-ntws-results-in-eurad.html

In line, with the outcomes of EURAD-1 where a double wing model was involving civil society members at different levels: a first wing of so-called Civil Society (CS) experts following closely the work packages, producing deliverables and organizing workshops to which a second wing of civil society members were invited to participate. This helped to have complementary views on the process as well as on the results for the civil society members. However, in order to achieve a better dissemination of the results to a larger audience it was proposed to envision a “third-wing” where more civil society members could be reached outside of EURAD’s ecosystem.

Therefore, in October 2024, the month where EURAD-2 started, the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) and the European Commission (DG Research & Innovation) 🇪🇺 jointly organise a conference called “Radioactive Waste Management: A Civil Society Perspective” on 17 October 2024 from 9:30 to 17:30, in Brussels.

Some members of NTW participated to this event and some were even invited to speak such as Peter Mihok (Slovakia) or Alexis Geisler-Roblin (France) in order to share the results of EURAD-1 from NTW’s perspective or to share the experience for civil society in a country like Slovakia.

The official kick-off meeting of EURAD-2 took place in Ghent 🇧🇪 with 220 participants representing 143 organisations from European and International countries 🌍🇪🇺 participating to 14 technical Work Packages (WP). NTW will coordinate a dozen of “CS” experts involved in the following 5 work packages:

1️⃣ PMO for “Programme Management Office”: coordination and implementation.

2️⃣ ASTRA: dedicated to alternative radioactive waste management strategies

3️⃣ FORSAFF: dedicated to waste management for SMR and future fuels.

4️⃣ CLIMATE: dedicated to the impact of climate change on nuclear waste management.

5️⃣ OPTI: dedicated to High Level Waste (HLW) repository optimisation including closure.

More information on EURAD website: https://www.ejp-eurad.eu/

As an NGO dedicated to ensure and increase transparency and public participation in nuclear safety and security in all fields of nuclear activities[1], Nuclear Transparency Watch (NTW) found it relevant to be involved in the European Joint Programme on Radioactive Waste Management (EURAD).

When EURAD started in 2019, the programme was foreseen to include activities and Interactions with Civil Society (ICS) in the perspective of the Aarhus Convention[2]. Therefore, it was understood that Civil Society (CS) could contribute to enhancing decisions on safety and security of Radioactive Waste Management (RWM)[3].

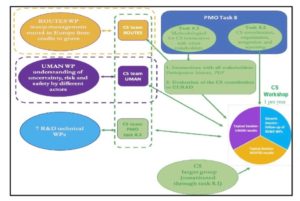

ICS activities in EURAD were structured based on a so-called “double wing” model[4] that was established and tested during the previous European projects SITEX II[5] and JOPRAD[6] following a specific vision and development plan[7]. This model allowed regular exchanges in between 13 CS experts involved in various EURAD Work Packages (WPs) and 22 CS larger group members attending yearly ICS workshops as described in the figure here below.

Figure 1 – Structure of ICS activities in EURAD

Figure 1 – Structure of ICS activities in EURAD

The yearly ICS workshops organised by the CS experts for the CS larger group were based on the results obtained by the CS experts from their work for the WPs labelled as “strategic studies” (ROUTES[8] and UMAN[9]) and their work for the WP PMO[10] which included:

Figure 2 – ICS workshop n°6 in Ljubljana (April 2024)

Between 2019 and 2024, 17 deliverables were published by the CS experts on various topics by stimulating interactions with the CS larger group and with the technical partners of EURAD [11]. Moreover, NTW has organized 17 workshops, participated to 30 EURAD events and contributed in around 40 EURAD documents. This iterative process helped to identify and deepen the knowledge in the main areas of concern for CS towards RWM.

First and foremost, the importance of sharing a culture for safety and security was underlined as a cornerstone for any fruitful pluralistic interaction on RWM. Therefore, based on previous studies such as SITEX II[12] a charter for fruitful interactions was established and used as an evaluation tool for the ICS activities in EURAD[13]. It was also considered relevant to update the existing studies on safety culture with more concrete examples of ways and situations where it can be enhanced[14]. Developing the “double wing” model into a “third wing model” was one of the propositions made[15], another was to continue the diversification of ways for CS to participate using existing tools such as the Pathway Evaluation Process (PEP)[16] – allowing pluralistic views on various RWM scenarios which had already proven to be very effective considering the feedback – or with new tools such as a visualisation tool designed by CS to be used as an interactive support enabling knowledge sharing and public participation[17].

Finally, to sustain and improve the Aarhus Convention pillars approved by the European Union[18] and the addition proposed by NTW in the BEPPER report[19], the concept of intergenerational stewardship[20] was studied as a means to maintain a safety culture through time until a final safe enough solution is found. This implies a recognition that the problem remains to be solved going against abandonment and amnesia.

Now that EURAD (2019-2024) is finished, a second phase of the programme (EURAD 2) is under final agreement with EC with NTW again foreseen as the coordinator for all CS organisations – which makes it important to share and evaluate the results of the first EURAD programme. This is why NTW has provided the following feedback for the evaluation of Euratom Research and Training Programme (2021-2025) which encompasses EURAD to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the Programme in the eyes of CS:

As an NGO involved in the Joint Programme on RWM EURAD, NTW has benefited from funding to represent civil society in the programme, in accordance with the first 2 pillars of the Aarhus Convention (access to information, access to participation) to help ensure the development of transparency and safety.

Results were obtained (e.g., production of deliverables on Transparency & Public Participation (T&PP) or Interaction with the Civil Society (ICS)) that envision better ways for interaction of different stakeholders involved in decision making procedures and research. Progress (e.g., double wing model of interaction and involvement in strategic studies) was made in understanding how to approach uncertainties through a shared culture for safety and security and what this could mean in the perspective of intra- and intergenerational stewardship.

However, there is still the need of sufficient structural and material support to develop a sustainable citizen engagement in a trustworthy environment independent from nuclear industry’s influence. Therefore, referring to the obligations under the Aarhus Convention art. 3(2), 3(3) and 3(4), it is necessary to include funds to develop civil society engagement structures to enhance civil society participation from a wider perspective and also in future research and training concerning the development of nuclear technology, including management of radioactive waste.

This is key to develop and implement processes, tools, knowledge, and relations that were previously established in the EURAD programme. If this is not continued, engagement towards transparency, public participation but also safety and security will suffer, as recognized by all stakeholders, who emphasized that participation of civil society in these research programmes is indeed indispensable in increasing safety.

List of publications per work packages in which NTW’s has been involved

PMO

ROUTES

UMAN

MODATS

[1] Nuclear Transparency Watch statutes:

https://www.nuclear-transparency-watch.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/NTW-statutes-2024-ENG.pdf

[2] Adopted on 25 June 1998, the Aarhus Convention is created to empower the role of citizens and civil society organisations in environmental matters and is founded on the principles of participative democracy. See: https://aarhus.osce.org/about/aarhus-convention

[3] EURAD – D1.14 Mid-term evaluation ICS activities and interactions EURAD participants and Civil Society: https://www.ejp-eurad.eu/publications/eurad-d114-mid-term-evaluation-ics-activities-and-experimental-model-interaction

[4] EURAD – D1.13 List of CS group members:

https://www.ejp-eurad.eu/publications/eurad-d113-list-cs-group-members

[5] SITEX-II is the acronym for “Sustainable network for Independent Technical Expertise of Radioactive Waste Disposal – Interactions and Implementation” (2015-2017). Its overall objective was the practical implementation of the sets of activities issued by the previous European research program SITEX (2012-2013). See: http://sitexproject.eu/

[6] JOPRAD is the acronym for « Joint Programming on Radioactive Waste Disposal” (2015-2017). The objective was to prepare a proposal for setting up of a Joint Programming that bring together at the European level, aspects of R&D activities implemented within national research programmes where synergy is identified. See: http://www.joprad.eu/about-joprad/rationaleobjectives.html

[7] The EURAD vision and EURAD deployment plan are two of the founding documents of EURAD.

All the funding documents are available here: https://www.ejp-eurad.eu/publications.

[8] https://www.ejp-eurad.eu/implementation/waste-management-routes-europe-cradle-grave-routes

[9] https://www.ejp-eurad.eu/implementation/wp10-understanding-uncertainty-risk-and-safety-uman

[10] https://www.ejp-eurad.eu/implementation/interaction-civil-society

[11] See the list of deliverables published in the Appendix.

[12] https://igdtp.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/SITEX-II_D4.1-Conditions-and-means-for-developing-SITEX-network_FINAL.pdf

[13] https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1WJW5URedhv4-Bvj5XeQAZscIYoocOHJ1/edit#slide=id.p1

[14] https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1IgDUkKpokcO0HIMn6ufBugfthjsXYaJN/edit#slide=id.p1

[15] https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1TK6e0og1-z-m-xiUOuf0c2_0Qh0gGJ3l/edit#slide=id.p1

[16] https://www.sitex.network/projects/

[17] https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/18kSmg9VybMynwHDRAtL7uKBtW9KrJjxW/edit#slide=id.p1

[18] Access to information, access to public participation and access to justice.

[19] Access to resources. See: https://www.nuclear-transparency-watch.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/NTW_Transparency_in_RWM_BEPPER_report_December_2015.pdf

[20] https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1hl4Za69yMx60DGuqEJ53qTxew4_OTUmr/edit#slide=id.p14

2023-07-31

Nuclear waste from NPPs remains an unsolved and highly dangerous problem, as spent fuel must remain isolated from the environment for a million years.

In an attempt to solve the nuclear waste problem, an EU-wide directive was introduced in 2011, the “Council Directive 2011/70/Euratom establishing a Community framework for the responsible and safe management of spent fuel and radioactive waste”. This directive tried to force EU member states to address the issue seriously, after this had been neglected for decades – thus immediately proving that nuclear waste has never been effectively dealt with.

The Joint Project has been active for years in monitoring the implementation of the Nuclear Waste Directive, especially with regard to transparency and opportunities for public participation.

The 2023 update of our report is available here.

In 2023, a new process of dialogue has started with the goal to experiment a joint work between civil society and IRSN on the basis of a co-constructed scenario (accident scenario in the operational phase of the repository or scenario of changes in the post-closure phase of the repository) with a view to a shared assessment of the associated safety issues.

Different types of participation were foreseen for the civil society from a general and continuous participation to a punctual and specific participation. In fact, three groups were established to consider three different themes during three different period:

Find out more about it there in French: DT-DAC-Cigeo_Bilan-perspectives_12_07_23

“A step change in European collaboration towards safe RWM, including disposal, through the development of a robust and sustained science, technology and knowledge management programme that supports timely implementation of RWM activities and serves to foster mutual understanding and trust between Joint Programme participants.” here is the description of the objective of EURAD and its activities on their website.

Further it is said that “EURAD Vision, SRA and Roadmap will be delivered through 5-year implementation phases broken down into a set of Work Packages, Tasks and Sub-Tasks.” In fact, this month is the beginning of the last year of this programme in which the Civil Society (CS) had a role to play on different Work Packages (WPs) represented by a diversity of CS experts from NTW:

During this last year NTW will work on an of its task in this programme which is “Dissemination” meaning sharing the inputs and work done with a larger audience than EURAD. A first glimpse of that could be found in the list of webinars below but more will come on the rest of the work done on this topic (deliverables, papers…):

On 05 May 2022 Nuclear Transparency Watch hold a webinar on Rolling Stewardship with the following speakers and program:

Purpose

Being engaged in the field of Radioactive Waste Management with a particular focus regarding transparency on nuclear safety and radiation protection, Nuclear Transparency Watch took part as Civil Society participant in the EC EURAD Research Programme in

June 2019. This participation, understood in the perspective of the Aarhus Convention, implied some involvement in several research projects that are, for two of them, designed on a strategical perspective opening to a more comprehensive understanding of socio-technical aspects of Radioactive Waste Management. In this context, it was felt that NTW would take advantage to develop its own thinking on Rolling Stewardship while liaising with interested partners of EURAD. A specific cooperation with the SITEX network (gathering Technical Support Organizations of Regulators of RWM and Civil Society Experts in the field) is also considered.

First speaker: Robert del Tredici

Robert del Tredici has a master’s degree in Comparative Literature at the University of California, and he has been a teacher for much of his life, giving courses in Photography, Drawing, Mythology, and History of Animated Film at the University of Calgary in Alberta and at Vanier College and Concordia University in Montreal. He is and has been a prolific graphic artist and documentary photographer: The People of Three Mile Island (1980), At Work in the Fields of the Bomb (1987), Closing the Circle on the Splitting off the Atom (1993); Linking Legacies (1995); From Cleanup to Stewardship (1997).

Second speaker: Marcos Buser

Geologist with a degree from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich, Marcos Buser is a consultant and expert who has been active for more than four decades in the management of industrial and radioactive waste projects, and a former member of several scientific commissions for the Swiss government, including the Swiss Federal Commission for Nuclear Safety. He was a member of the Stocamine steering committee.

On 23 March 2022 Nuclear Transparency Watch hold a webinar on Rolling Stewardship with the following speakers and program:

Purpose

Being engaged in the field of Radioactive Waste Management with a particular focus regarding transparency on nuclear safety and radiation protection, Nuclear Transparency Watch took part as Civil Society participant in the EC EURAD Research Programme in

June 2019. This participation, understood in the perspective of the Aarhus Convention, implied some involvement in several research projects that are, for two of them, designed on a strategical perspective opening to a more comprehensive understanding of socio-technical aspects of Radioactive Waste Management. In this context, it was felt that NTW would take advantage to develop its own thinking on Rolling Stewardship while liaising with interested partners of EURAD. A specific cooperation with the SITEX network (gathering Technical Support Organizations of Regulators of RWM and Civil Society Experts in the field) is also considered.

First speaker: Niels Henrik Hooge

Master of Laws and Master of Arts in Philosophy. Interested in environmental and sustainability for a long time he has manifested itself in activism, cooperation with green NGOs in Denmark and abroad, as well as in many types of writing. In addition to editorial staff work in Danish environmental magazines, he has published several books, including most recently the novel “Kosova” (2016) and the poetry collections “Grøn nation” (Green Nation, 2015), “Miljødigte” (Environmental Poems, 2018) and “Miljødigte 2” (Environmental Poems 2, 2019).

Second speaker: Gordon Edwards

Ph.D. in Mathematics and Master of Arts in English Literature. Gordon Edwards has been a Professor of Mathematics and Science during all his career during which he did many publications in that field but not only. From 1970 to 1974, he was the editor of Survival magazine. In 1975 he co-founded the Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility and has been its president since 1978. Edwards has worked widely as a consultant on nuclear issues and has been qualified as a nuclear expert by courts in Canada and elsewhere.

By Nadja Zeleznik – Nuclear Transparency Watch

Slovenia and Croatia share the nuclear power plant Krško (NEK) which was constructed as a joint venture during 1970-ties in the socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia as part of the larger nuclear programme on the use of nuclear energy. NEK is a two loop PWR Westinghouse (USA) design with all supporting infrastructure on site, including the buildings for radioactive waste and spent fuel management. Licensing was performed by the Republic Committee for Energy, Industry and Construction as the responsible authority in Slovenia. All other authorities were coordinated by this Committee, including the Expert committee on nuclear safety with its Technical Support Organizations. A safety report with safety analyses was mainly based on the provisions from USA NRC legal framework because the plant was of USA design. Trial operation was granted in 1981, in 1983 commercial operation started, and a license for normal operation was obtained in 1984 under Yugoslav and Slovene legislation.

Operator NEK d.o.o. is organized as a limited liability company in 100 % state ownership from entities of two republics: 50 % is owned by GEN energija d.o.o from Slovenia and 50 % by HEP d.d. from Croatia, both in 100 % ownerships by their states and the successors of the initial investors. The owners of NEK are equally responsible for ensuring all material and other conditions for safe and reliable operation of NPP, whereas the regulation and supervision of nuclear and radiation safety for NEK is the sole responsibility of the Republic of Slovenia. The regulatory framework for nuclear and radiation safety consists of the Ionizing Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Act with a set of regulations and decrees that are harmonised with international developments. All other legal requirements are incorporated in other legislation in Slovenia. The responsible authorities are primarily the Slovenian Nuclear Safety Authority (SNSA) within the ministry responsible for environment and the Slovenian Radiation Protection Administration (SRPA) within the ministry responsible for health.

After the breakup of Yugoslavia in 1991, NEK continued to operate under the legal framework of the Republic of Slovenia, although co-ownership with the Republic of Croatia was recognized and never argued but was not well defined under the new legal systems of both countries. Next to one major dispute on the energy supply which finished with lawsuits by both owners, the governments agreed to define in more details mutual relations regarding the status of NEK, its exploitation and decommissioning and adopted in 2001 the Agreement between the Government of the Slovenia and the Government of the Croatia on the Regulation of the Status and Other Legal Relations Regarding the Investment, Exploitation and Decommissioning of the Krško NPP (Intergovernmental Agreement – IA), ratified by both parliaments in 2003. The most vital points in the IA are the establishment of NEK decision making bodies, with as most important the Intergovernmental Commission (IC), in order to monitor the implementation of the IA, responsibilities in relation to the production of electricity, transmission, costs, recruitment, education, contractors and support for equal opportunities for workers. A very important part of the IA is devoted to decommissioning of NEK and radioactive waste and spent fuel management, where several provisions are agreed:

For improvement of safety and due preparation of NEK lifetime extension, a dry spent fuel storage is under development with the construction license issued in December 2020. Under pressure from environmental organisations, an environmental impact assessment (EIA) was carried out, and NEK has to take into account also some measures and conditions to mitigate adverse effects including zero base monitoring before facility construction, protection of soil and water, and emergency preparedness.

The Waste Manipulation Building intended for storage and further manipulation of radioactive waste in drums was constructed in 2018. This happened without EIA.

NEK’s lifetime extension for 20 years, which is inevitably linked with radioactive waste and spent fuel generation, was initiated. SNSA took in 2012 a decision in principle, referring to the results of two Periodic Safety Reviews in 2023 and 2033. However, such an approach did not follow non-nuclear legislation and NEK had to file an application for lifetime extension to the responsible body ARSO in 2016. Only after an appeal from NGOs and a judgement from the Administrative Court in October 2020, ARSO decided that for the NEK lifetime extension an EIA is obligatory. The process will take several years, but information and participation will be assured.

The long-term radioactive waste and spent fuel management from NEK is defined in the Programme of NPP Krško Decommissioning and spent fuel and Low and Intermediate Level Waste (LILW) Disposal (DP) which was so far adopted with two revisions. The main purpose of the DP is to propose technical solutions, to estimate decommissioning and radioactive waste and spent fuel disposal costs for NEK, and to calculate annual instalments for devoted funds in Slovenia and Croatia. DP Rev.1 was approved by the Intergovernmental Commission, adopted by Slovenian government and Croatian parliament at the end of 2004. In 2011, the DP rev.2 was developed with new boundary conditions, including the option of NEK lifetime extension, but this was never adopted. There were no clear statements why there was no agreement. DP rev. 3 was developed again under new boundary conditions (like the NEK lifetime extension, dry SF storage as part of NEK’s operation, so only three projects were still to be addressed: NEK decommissioning, LILW disposal and SF disposal) and was adopted in 2020 by the same main authorities: the IC, the Slovenian Government and the Croatian Parliament. A joint LILW repository was rejected by the council of the municipality of Krško, so in the DP Rev. 3 two separate radioactive waste disposals are taken into account: one in Slovenia on the selected site Vrbina, next to NEK, and one in the potential radioactive waste centre Čerkezovac in Croatia, although the latter is still in the licensing process. Therefore, the division of operational and decommissioning radioactive waste is analysed and included in this revision, starting with the removal of existing waste from NEK in 2023. Regarding spent fuel disposal, a joint solution is still foreseen between the two states. During the development of the DP, no public participation took place and all decision making was entrusted to the Intergovernmental Commission and its advisory committees.

In between, the Slovenian LILW repository has evolved, and a site licence was obtained in 2010 for a modular silo version of the repository at the Vrbina, Krško site, which is just next to the NEK. Information and public participation were broader than required and during site selection local partnerships were functioning, although later ceased. In the EIA report, two silos were included, thus creating the possibility that the disposal contains all radioactive waste generated at NEK. The construction licencing procedure is now in its final stage, while in parallel an EIA procedure with prescribed public participation, including a public hearing and 30 days for comments and suggestions, and a transboundary EIA (including also Croatia) is performed.

Until the adoption of the IA in 2003, the management of different issues of NEK were also bringing disagreements between the co-owners. One of the major ones was the issue of costs for NEK operation and the related decommissioning, radioactive waste and spent fuel management, to be set in a dedicated fund. The dispute ended with lawsuits and with the decision that Slovenia had to pay a total of around 40 million € due to the non-supply of electricity to Croatia in 2002 and 2003.

After the adoption of the IA in 2003, relations have become much more defined with procedures on how to approach in case of divergences. For on-site radioactive waste and spent fuel management, a basic decision-making process is in place and no disagreement is reported publicly (e.g., in media). However, for several new radioactive waste and spent fuel buildings on site or even for the lifetime extension of the NPP, NEK tried to minimise public participation. EIA processes started only after successful appeals by NGOs, administrative court rulings and new decisions of ARSO: the EIA for the Waste Manipulation Building, an EIA process for the Dry Spent Fuel Storage, and an EIA for the NEK lifetime extension.

With regards to the long-term decisions for the radioactive waste and spent fuel management from NEK operation and future decommissioning, the issues are less conclusive and more complex. The main decision-making body defined in the IA is the Intergovernmental Commission. The basic documents that define the future decommissioning and disposal activities are the Programme of radioactive waste and spent fuel Disposal and Decommissioning, which should be developed every five years. The mechanisms for development of those programmes are also in place: two responsible organizations – ARAO and the Fund – with sufficient knowledge and resources for development of work, based on a Terms of Reference (ToR), adopted by the IC and further confirmed by the Slovenian Government and Croatian Parliament. However, the process of regular adoption of new revisions every five years was not successful. After the DP, Rev. 1, adopted in 2004, the Revision 2 of the DP scheduled to be adopted in 2009, although started on time, was never adopted. Only in 2020, Revision 3 of the DP was adopted, but the joint solution for LILW management was not agreed and two separate LILW repositories are planned for. The reasons for rejection of a joint LILW repository establishment were never set out in writing, but the basic principles as proposed by the advisory body to the IC (on safety of solutions, disposal of all radioactive waste in Slovenia and Croatia, optimization of costs and equal participation of entities from both countries) were already rejected at the level of the Krško municipality and were just taken over by the IC.

According to the IA, the decision making is limited to the official representatives of both countries, namely the members of the IC and its advisory body (this time called the Implementation Coordinating Committee), basically represented by appointed high ranking politicians or heads of responsible organizations. There is no other decision making foreseen, as programmes are seen as a kind of strategic documentation. However, there is a question whether such documents should also be also open for public participation (in terms of any kind of environmental assessment or other unofficial discussions) and would such broadening of transparency increase the acceptability of projects. Arguments for such public participation can be found in the Aarhus Convention, article 7, which obliges public participation for plans, programmes and policies related to the environment, the Kiev Protocol to the Espoo Convention on strategic environmental assessments and the EU Strategic Environmental Assessment Directive 2001/42/EC.

Typical for NEK activities, transparency in terms of nuclear safety and Waste Directive requirements remains an issue of concern: the approach used is to go for construction licenses to the Ministry of Environment and Spacial Planning, where SNSA provides consent for the nuclear safety and radiation protection part. Such an approach definitely shortens the procedure, but also excludes any public participation. Only lately we see a change, basically due to the appeals from NGOs to require EIA procedures for projects.

In relation to development of long term radioactive waste and spent fuel management solutions for NEK, the implementation of the IA is not so effective and successful, the functioning of the IC is limited. Members of the IC are changing with changing governments: the lead from each country is the responsible minister, a state secretary in the ministry and some other state officials. So the IC changes after each election. It would be important to stabilise future functioning of the IC and to think about professionalisation of the body. If the members would not change every two years (the current rate of government changes in Slovenia), they would be much more knowledgeable in the area, and also much more independent in decisions. Currently, the IC is perceived as a political body and also the broader context of relationships between the countries impacts its functioning (like the disputed border on the sea).

Transparency including information provision and public participation (not to mention access to justice) of developed programmes decided by the IC is really a weakness. Decisions are taken by the IC, on websites there is no further information on how decisions have been taken, the public is informed on press conferences about the outcomes. The programmes are published only after they are adopted and there is no public participation. However, individual projects (like the LILW repository) are going through all steps as prescribed in legislation, including an EIA process. The Law on environmental protection already now requires that for strategies or plans, a strategic environmental assessment (SEA) should be performed, also including public participation for important national strategies. Following the definitions in the Aarhus Convention, the Kiev Protocol to the Espoo Convention and the SEA Directive, the DP has to be understood as a national programme which directs radioactive waste and spent fuel management from NEK.

An open discussion on the shared option and a structured dialogue with interested parties from both countries would enable a more flexible approach in which disagreement could be addressed and potentially mitigated and solved.

By Michal Daniska (Nuclear Transparency Watch)

Since 2013 (at the latest) foreign LLW and VLLW has been treated at RW Treatment and Conditioning Technologies in Jaslovské Bohunice (RW TCT), Slovakia, mainly through incineration. Hundreds of tons of RW from the Czech republic, Italy and Germany have been incinerated or contracted for incineration at RW TCT (see the sec. 4.2.3 for details). The transformation of RW TCT from the exclusively national facility to an international RW treatment provider was done without prior consultation with, and approval by the public and municipalities which, according to, e.g., one of the mayors[1] might have found out about it only in 2018 (i.e., after approx. 5 years). The foreign RW share incineration varied between approx. 35-45% during 2015-2019 and exceeded 50% for the first time in 2020. Foreign RW treatment, especially by means of incineration, was originally categorically rejected by the vast majority of the affected municipalities. However, multiple municipalities later turned their position by 180 degrees on the condition, among others, that they received economic and non-economic incentives[2]. Unusually strong refusal arose also among the public, e.g., approx. 3 000 citizens signed a petition against capacity increase of RW TCT and demanding prohibition of foreign RW treatment in Slovakia. Meanwhile, the operator applied for an increase of the RW TCT treatment limits from 8343 to 12663 t/year in total (including an increase from 240 to 480 t/y by incineration) and a second incineration plant has been constructed. There is some evidence supporting an opinion that Slovakia itself does not need such an increase of treatment (or at least incineration) capacities and a suspicion that the second incineration plant might be purpose-built to better fit the specific RW from the Caorso NPP, Italy. The Slovak Atomic Act allows import, treatment and conditioning of foreign RW on condition that the radioactivity level of the imported RW equals the radioactivity level of the reexported (after treatment and conditioning) RW. Since the change of government in March 2020, the new Minister of Environment has been trying to ban foreign RW incineration by law. On 6 October 2021, the Slovak Parliament approved a bill which aims at banning future contracts for incineration of foreign RW on the Slovak territory. The already signed contracts for incineration of foreign RW from Italy (617 m3 and 865 tons) and Germany (21.7 t) will not be affected by the bill[3].

RW TCT is a part of a larger nuclear site near Jaslovské Bohunice, Slovakia, that also includes NPP A1 and V1 (both being decommissioned), NPP V2 (in operation), interim SNF storage and other nuclear installations. In addition, a new nuclear reactor is planned in this locality (EIA process completed in 2016). NPP A1, commissioned in 1972, was the first NPP in the former Czechoslovakia. Being operated only for 5 years, NPP A1 was permanently shut down after two serious accidents in 1976 and 1977. Shortly after the process of decommissioning had slowly begun and continues currently. The core of the RW TCT was designed to ensure the process of treatment of RW produced during the decommissioning of NPP A1. As a result of gradual development, the RW TCT in its current state includes e.g., two incinerators for solid, liquid RW and saturated sorbents; facilities for super-compaction of solid RW; metallic RW remelting; fixed RW pre-conditioning; concentration of liquid RW; solid RW sorting; bituminisation and other installations. The first of the two incinerators is a shaft furnace type (as in Seibersdorf, Austria), was built between 1993-1999 and has been operated since 2000. The second incinerator has a rotary kiln, its project dates back to February 2017 at the latest, has been constructed between 2019-2021 and is going to be commissioned soon.

RW TCT is owned and operated by JAVYS (Jadrová a vyraďovacia spoločnosť = Nuclear and decommissioning company), a state-owned stock company (the Ministry of Economy of the Slovak republic holds 100% of the company stocks). Originally, before JAVYS was founded in 2005, RW TCT belonged to Slovenské elektrárne (i.e., “Slovak power plants”) company. Prior to its privatisation in 2006 Slovenské elektrárne had been a state-owned company which operated all the power plants in Slovakia including the nuclear ones and the related infrastructure (e.g., RW and SNF management facilities). JAVYS was founded by separating it from Slovenské elektrárne in 2005. JAVYS was not a subject of privatisation and, as a result, has remained completely state-owned. At the time of its founding JAVYS consisted of selected nuclear assets in which the Italian ENEL company, the winner of the business competition for privatisation of the Slovenské elektrárne, was not interested. In addition to RW TCT, these assets included the NPP A1 and V1 (and their decommissioning), the Interim SNF storage (in Bohunice) and the National repository for LLW and VLLW in Mochovce. At the moment, JAVYS is also responsible for the deep geological repository project, holds the de facto monopoly position in interim storage of Slovak SNF, decommissioning and management of RW and, through a 51% share, takes part in the project of the new NPP in Jaslovské Bohunice.

At RW TCT, the foreign RW is treated mainly by incineration which, until the second incinerator is commissioned, takes place exclusively at the first incinerator. The incineration of foreign RW dates back to 2013 when 8.8 tons of Czech RW were incinerated. In 2012 the volume of the incinerated Slovak RW reached its historical minimum after it had decreased from approximately 140t to 50t a year between 2007-2012. Gradually, the Nuclear regulatory authority of the Slovak republic (NRA SR) issued permissions for incineration of (1) 39.64t RW from NPP Temelín and Dukovany, Czech republic (31.10.2013); (2) 7t +16m3 institutional RW from Italy (03.09.2015); (3) 145.2t RW from NPP Temelín and Dukovany, Czech republic (27.11.2015); (4) 800t ion-exchange resins in urea formaldehyde and 65t sludge from the decommissioned NPP Caorso, Italy (04.06.2018); (5) 21.7t institutional RW from Germany (22.01.2019) and (6) 617m3 institutional RW from Italy (25.01.2019). Incineration of approx. 1600 tons of foreign RW (Czech rep., Italy, Germany) was contracted in total, out of which approx. 300 tons have already been incinerated between 2013 – 2020. In comparison, approx. 1100-1200 tons of Slovak RW were incinerated between 2007-2020. In the period 2015-2019 approx. 110-130t of RW in total were incinerated annually, out of which the Slovak RW represented 60-85t, the share of foreign RW at incineration oscillated between 34-46% (43-56 tons annually) and exceeded 50% for the first time in 2020. Although the current legal limit for RW incineration is 240 t/year, according to JAVYS it is in practice not technically feasible to incinerate more than 130-150 t/year of RW at the first incineration plant. In case the capacity increase (in case of incineration from 240 t/year to 480 t/year) is approved and the second incineration plant becomes operational, the volume of incinerated RW in practice may increase to approx. 420-460 t/year (i.e., approx. 3 to 5-fold increase if compared to the current state), and the foreign RW share at incineration might exceed 70%[4].

The public did not participate in the authorization processes for import and incineration (treatment) of foreign RW in Slovakia held by NRA SR which resulted in the six permits mentioned above. The available information does not indicate that mayors of the affected municipalities were aware of the ongoing foreign RW incineration until about 2018[5]. However, at least since 2014 the mayors have been considering the risk of such activities, although only as a theoretical option in the future. During various EIA processes, the municipalities regularly (as a precaution) expressed their disapproval of foreign RW treatment in the Jaslovské Bohunice locality until 2019. Nevertheless, we have not found any evidence that the municipalities were explicitly notified of the ongoing foreign RW treatment (incineration) during the EIA processes before 2017/2018. The EIA process “RW processing and treatment technology by JAVYS, a.s. at Jaslovské Bohunice location” (December 2012 – November 2014), during which the already existing and operated RW TCT were assessed for the first time on the basis of modern EIA legislation, might be used as a particular example. During a public hearing, which took place in March 2014, the mayors directly and indirectly asked about the possibility of treatment of RW from locations other than Jaslovské Bohunice. In response JAVYS did not inform about foreign RW treatment (e.g., incineration) that had already been carried out (8.8 tons RW from the Czech Republic incinerated in 2013) or that which had already been contracted. The statement of JAVYS was formulated in a conditional way, as if the treatment of RW for other companies (aside from RW from Mochovce NPP) was not a reality yet. Although it was admitted that contracts for RW treatment and conditioning were being sought, it was not directly mentioned that the RW would come from abroad. In addition, “foreign RW treatment” was not even once explicitly mentioned, neither in the EIA plan, EIA report nor in the minutes from the public hearing. Finally, the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) from this EIA process (issued in November 2014, with minor changes valid until today) explicitly states that RW TCT serves the treatment and conditioning of VLLW, LLW and ILW from (1) decommissioning of the Slovak NPPs A1 and V1; (2) operation of Slovak nuclear installations; or (3) institutional RW (IRW) and captured RW (CRW). The list of purposes does not explicitly mention treatment (incineration) of foreign RW. In March 2021 the Slovak Ministry of Environment stated that “the ongoing foreign RW treatment (incineration) is inconsistent” with the EIS mentioned above[6]. However, the treatment of foreign RW at RW TCT continues.

It was not until the beginning of 2018 that information on the treatment (incineration) of foreign RW resonated for the first time among municipalities and a part of the public. There were two main sources – (1) the press conference of then opposition MPs Mr. Igor Matovič and Mr. Marek Krajčí about incineration of RW from the decommissioned Italian NPP Caorso and their failed attempt to ban incineration of foreign RW by law (February 2018) followed by (2) publishing the EIA plan “Optimisation of treatment capacities of radioactive waste treatment and conditioning technologies JAVYS, a.s. at Jaslovské Bohunice” (March 2018) where foreign RW treatment was mentioned among the purposes of RW TCT. However, the treatment and especially incineration of foreign RW gained more significance and repeated media attention only in the middle of 2020, after the February 2020 elections and the consequent change of government (Mr. Matovič and Mr. Krajčí became the Prime Minister and the Minister of Health, respectively).

The environmental impact assessment (EIA) project “Optimisation of treatment capacities of radioactive waste treatment and conditioning technologies JAVYS, a.s. at Jaslovské Bohunice” stands for capacity increase of RW TCT, from 8343 to 12663 t/year in total (all technologies). It also covers the second incinerator and an increase of the incineration limit from 240 to 480 tons per year (corresponding to the real incinerated volume increase from approx. 130t/y, the technical limit of the first incinerator, to approx. 420-460t/y if both incinerators are in operation); capacity increase of the metallic RW remelting from 1000 to 4500t/y, and so on. In April 2018, the vast majority of the municipalities categorically refused foreign RW treatment, especially incineration, and the proposed RW TCT capacity increase, reasoned with arguments of (protection of) a healthy environment for their citizens (not by unmet financial requirements). An individual EIA process for the second incinerator was only launched in September 2018 under the name “Optimisation of incineration capacities of the nuclear installation RW Treatment and Conditioning Technologies”, thus accelerating the authorization process of the second incinerator. JAVYS justified the second incinerator with an expected approx. 50% increase in production of domestic combustible RW[7] in 2020-2023 and the necessity to have an operational incinerator capacity within the assessed limit of 240 tons/year (the technical limit of the first incinerator is approximately 130t/y only) in order to “meet emerging requirements for RW treatment from decommissioning and also from the operation of NPPs in the Slovak Republic”. Based on this justification, the majority of the municipalities approved the second incinerator providing that the limit 240t/y (for both incinerators together) is preserved and no foreign RW is incinerated at the second incinerator. These conditions, explicitly accepted by JAVYS, were transposed into the final ruling issued in this individual EIA process. Under these conditions, the municipalities did not obstruct the authorisation process and already in June 2019 the NRA SR could have issued a construction permit and the construction of the second incinerator could have begun.

On 24.03.2021 the Ministry of Environment of the Slovak republic issued the EIS no. 417/2021-1.7/zg from the EIA process “Optimisation of treatment capacities of radioactive waste treatment and conditioning technologies JAVYS, a.s. at Jaslovské Bohunice” which, however, has not entered into force yet due to appeals lodged. This EIS approved the proposed capacity increase and set no restrictions on foreign RW treatment. The Ministry of Environment argued that 1.) it cannot interfere with or restrict business activities if significantly negative impact on the environment had not been demonstrated and 2.) there is a constitutional right to engage in business and other gainful activity[8]. Once the EIS from the EIA process “Optimisation of treatment capacities of radioactive waste treatment and conditioning technologies JAVYS, a.s. at Jaslovské Bohunice” comes into effect, the EIS from EIA process “RW processing and treatment technology by JAVYS, a.s. at Jaslovské Bohunice location” and the ruling from the individual EIA process for the second incinerator expire. Therefore, the restriction prohibiting incineration of foreign RW at the second incinerator will expire as well, unless the EIS no. 417/2021-1.7/zg is amended as a result of the appellate procedure and such restriction is added to the EIS.

It is important to point out that JAVYS agreed to exclude foreign RW treatment at the second incinerator in December 2018, i.e., in a situation when the EIA process “Optimisation of treatment capacities of radioactive waste treatment and conditioning technologies JAVYS, a.s. at Jaslovské Bohunice” was already in progress and permits for incineration of foreign RW valid today had already been issued by NRA SR or the permits had already been requested. Also, the condition prohibiting incineration of foreign RW will be de facto applied only after the second incinerator is commissioned.

In 2019-2020 the volumes of incinerated Slovak RW reached approx. 60 tons per year (1/8 of the proposed increased limit 480t/y) which means an approx. 25% decrease if compared to the period 2016-2018 (approx. 80-85 t/y). This data does not seem to be in accord with the statement of JAVYS from 17.12.2018 when it expected an approx. 50% increase in Slovak RW production from NPP decommissioning in the period 2020-2023 and used it as the primary reason for justification of the second incinerator[9]. Also, according to the National policy for management of SNF and RW in the Slovak republic (2015), the current capacity of RW treatment lines (i.e., without the second incineration plant) is sufficient (with reserves) for treatment of RW from both operation and decommissioning of the Slovak nuclear installations. These conclusions are consistent with the data volumes of incinerated Slovak RW (60-85 t/y in 2015-2019) which is significantly below the technical capacity of the first incinerator (approx. 130t/y).

There were two public hearings during the EIA process “Optimisation of treatment capacities of radioactive waste treatment and conditioning technologies JAVYS, a.s. at Jaslovské Bohunice” – on 26.08.2019 and 16.12.2019. Among others, JAVYS declared on 26.08.2019 foreign RW treatment as “a complementary activity” (compare this to a 34-46% share of foreign RW at incineration in 2015-2019 and a possible expected increase to over 70% in the future); on 16.12.2019, JAVYS, among others, claimed that foreign RW share at incineration was 12% only The public obtained data about volumes of incinerated domestic and foreign RW only in the middle of 2020 (e.g., through a request of information sent to NRA SR[10]).There have been attempts to obtain more detailed data about incineration of foreign RW (e.g., activity streams, production and management of the secondary RW) which, however, have led to very limited success.

Currently, after a position change in 2019, the majority of the affected municipalities and the association of municipalities explicitly approved both the RW TCT capacity increase and foreign RW treatment (up to 30% share) on the condition (among others) that new economic and non-economic incentives for municipalities in the region are established. Two county towns (Hlohovec and Piešťany) and some other municipalities continue opposing the project. Approx. 3000 citizens signed a petition against capacity increase of the RW TCT and demanding a prohibition of foreign RW treatment in Slovakia.

The affected villages that now consent to the project received 10000€ each from JAVYS in December 2019. On the contrary, the opposing affected villages received only 2500€ or 0€[11]. The following year in December 2020, after this fact was published in the media, all 9 affected municipalities received 10000€ each from JAVYS.

The Caorso contract for incineration of more than 30-year-old 800 tons of ion-exchange spent resins in urea formaldehyde and 65 tons of radioactive sludges (5881 tanks) from the shutdown Italian NPP Caorso, holds an exceptional position among the 6 contracts for foreign RW incineration at RW TCT. The main reason is the allegedly challenging nature of this RW is that it is said to lead to difficulties during incineration in the shaft furnace of the first incinerator and a suspicion that the second incinerator with a rotary kiln might be purpose-built to better fit the RW from Caorso and thus overcome these difficulties[12]. These doubts can be supported by (1) the original construction contract stating that the second incinerator must (with special regards) be capable of incineration of ion-exchange spent resins in urea-formaldehyde which shall be proven by successful hot tests with 100 tons of ion-exchange resins in urea-formaldehyde and 20 tons of other RW. In May 2021 the NRA SR explicitly confirmed that “exactly the urea-formaldehyde resin represents the foreign RW”[13]; (2) the Caorso contract was signed in 2015, but hot tests at the first incinerator took place only in 2019, after a brand new pre-conditioning line was commissioned; (3) the hot tests at the first incinerator took almost half a year (21.01.2019 – 02.07.2019) and large volumes (43 tons reduced by preconditioning to 15,5 tons) were incinerated; (4) almost a threefold reduction of RW mass through pre-conditioning; (5) the contracting process for construction of the second incinerator took place 20 months after the Caorso contract was signed (February 2017 vs. June 2015); (6) incineration at the second incinerator does not result in alpha cross-contamination of the (foreign RW) ashes; (7) the residual capacity of the first incinerator (i.e. after incineration of the Slovak RW) is approx. 60-80 t/y, which does not seem to be sufficient to meet the Caorso contract deadline in 2023 (assuming the contract volume 865 ton and also other contracts, e. g. 617m3 of institutional RW from Italy).

However, a direct connection between the second incinerator and the Caorso contract has not been confirmed, neither by JAVYS nor by the nuclear regulator NRA SR. Transparency is deficient not only in the clarification of the relation between the Caorso contract and the second incinerator (and the preconditioning line), but also in the Caorso contract itself. The Caorso contract was, after a significant portion of relevant data had been redacted, published online in November 2020.

Since the change of government in 2020, the new Minister of Environment, Mr. Ján Budaj, has been trying to ban foreign RW incineration by law. These efforts encountered a significant obstacle represented by huge financial penalties in case the Caorso contract is terminated. Different positions of the Ministries of Environment and Economy on this topic led in February 2021 to a compromise proposal that the ban would not affect the already signed contracts for foreign RW incineration. A corresponding legislative bill was submitted in the Slovak parliament at the end of May 2021. On 6 October 2021, after significant changes were made to the wording of the bill at an advanced stage of discussion in the Parliament, the Slovak Parliament approved a bill which aims at banning future contracts for incineration of foreign radioactive waste on the Slovak territory[14]. After the president of the Slovak republic signed the bill on 25 October 2021, which will come into effect on 1 January 2022. The already signed contracts for foreign RW incineration will not be affected by the bill. This concerns 617 m3 and 865 tons of RW from Italy and 21.7 t from Germany, i.e. amounts that significantly exceed the volumes of incinerated domestic RW (about 60 – 85 tons annually during the period 2016-2020).

Correct and complete impact assessment of the foreign RW treatment is a challenging task. For example, tracking down where all foreign radionuclides might end up could be highly relevant. One of the reasons is that the ratio of radioactivity retained in ash after incineration compared to radioactivity of the input RW is variable and significantly below 100% (on average approx. 60% in the period March 2020 – October 2021). At the same time wastewater from wet filtration of flue gases from RW incineration, which might contain a significant share of foreign radionuclides, ends up permanently in the RW repository in Mochovce. In order to analyse the fraction of foreign radionuclides that remain in Slovakia and how these missing radionuclides are replaced by Slovak radionuclides the public requested, mostly unsuccessfully, data about radioactivity streams during RW preconditioning, incineration and post-treatment (e.g., how much radioactivity is carried to the wastewater) and the production of secondary RW. This data is crucial in order to analyse the impact of the foreign RW treatment, especially by incineration. However, when requested, the nuclear regulator NRA SR could not provide (did not have) detailed data about activity streams in the treatment process. The data cannot be obtained from JAVYS either, since it claims not to be a liable entity according to the Slovak Freedom of Information Act.

Financial impacts should be assessed in detail as well. For example, the foreign RW owners do not participate in the future decommissioning of the RW TCT (especially the incinerators and the pre-conditioning line). The corresponding costs are expected to be covered by the National Nuclear Fund that collects money from Slovak electricity consumers. It could be worth analysing whether the Slovak taxpayers do not subsidise the foreign RW treatment in any (hidden) way (incl. construction, operation and future decommissioning costs, indirect costs – e.g., if the incinerator lifetime was negatively affected by the foreign RW treatment).

One can also argue that foreign RW treatment might challenge the ALARA principle. Slovakia is not legally or morally responsible for foreign RW, so it is reasonable not to incinerate/treat it and thus avoid any kind of unnecessary negative effects or risks. The Public Health Authority of the Slovak republic, Section of radiation protection justified its 2017 legislative proposal to ban foreign RW incineration by this argument.

The crucial issues here are transparency, public access to information, evidence-based decision making and effective public participation, which, among others, represent some of the key principles of the Aarhus Convention and the European Council Directive 2011/70/EURATOM. We consider it important to take into account that JAVYS is not a private but state-owned company and that most technologies of the RW TCT received necessary permits when the public and the municipalities implicitly assumed that RW TCT served management of the Slovak RW only and RW from decommissioning of NPP A1 in particular. First of all, the public discussion about foreign RW treatment should have taken place prior to RW treatment services being possibly offered to foreign customers, not years after foreign RW treatment in Slovakia started. The eventual ongoing discussion, which was initiated mainly by the public and the municipalities, is strongly affected by the risk of huge financial penalties in case the already signed contracts are terminated. This significantly reduces the set of options (de facto) available for discussion and subsequently impacts the results.

The second important issue are the difficulties in access to (objective and complete) information, information verification and consulting with independent experts in the case of the public and the municipalities. In practice the main source of information about activities at the nuclear site J. Bohunice for the general public are the corresponding EIA processes, since the EIA documentation is easier-to-read for non-experts, is published online and often also the public hearings take place in the affected municipalities. On the other hand, documentation from processes held by the nuclear regulator NRA SR is expert-oriented, can be accessed usually only via physical inspection and sometimes is even declared confidential. However, even in the EIA processes, the effectiveness of public participation is limited by information asymmetry between the public and municipalities on one hand, and the project proposer on the other. In case of nuclear installations, this asymmetry is further enhanced because of higher complexity of the problem. Due to limited time, expertise and financial resources the public and municipalities are reliant mostly on information provided by the project proposer, either in the EIA documentation or in reactions to additional questions (raised e.g., during the public hearing). Consultations with independent experts appear to be a theoretical option only, not only because of short procedural deadlines and financial constraints, but also due to a lack of suitable independent nuclear experts and/or insufficient free capacities of these experts. Even the Ministry of Environment failed while attempting to obtain an additional independent (expert) opinion on the EIA report within the EIA process “Optimisation of treatment capacities of radioactive waste treatment and conditioning technologies JAVYS, a.s. at Jaslovské Bohunice” in autumn 2020[15].

Effective public participation in the decision-making process requires that the public and municipalities are provided with correct and complete information about the project, its impacts and purpose as well as tools for easy information verification. The public should not be dependent on extensive and time-consuming investigation and information verification based on independent sources. The situation is negatively affected by the fact that JAVYS claims not to be a liable entity with respect to the Slovak Freedom of Information Act. This is difficult to understand, since this company is state-owned, carries out a public service and receives millions of euros from the public budget (through the National Nuclear Fund) each year, de facto holds a monopoly position in management of RW and SNF in Slovakia and, on top of that, it is also responsible for the project of the Slovak deep geological repository.

If the decision-making process is to be evidence-based, the project proposer shall be required to support all claims by objective and verifiable data.

Besides the deficiency in transparency and public participation and limited public access to information, the challenges related to the foreign RW treatment include (1) missing publicly available analyses of radioactivity streams, secondary RW production and corresponding data on the fraction of foreign radionuclides that remain in Slovakia and how these missing radionuclides are replaced by Slovak radionuclides; (2) non-participation of the foreign parties in the future decommissioning of RW TCT and in the legal responsibility in case of accidents or other indirect impacts; (3) missing publicly available detailed financial analyses including also of all indirect costs (it could be worth analysing whether the Slovak taxpayers do not subsidize foreign RW treatment in any (hidden) way); (4) reasonable doubts about the need of the second incinerator (in perspective of the Slovak needs) and clarification of the relation between the Caorso contract and the second incinerator (and the preconditioning line); (5) possible conflict of interests – e.g. some members of municipal councils employed at JAVYS; (6) financial power asymmetry between the proposer and the public. The distribution of substantial financial benefits from JAVYS to the affected municipalities in 2019 is highly correlated to the (dis)approval of the proposed RW TCT capacity increase by these municipalities; (7) law enforcement – the Ministry of Environment confirmed that “the ongoing foreign RW treatment (incineration) is inconsistent” with the still valid EIS. However, the treatment of foreign RW at RW TCT continues.

[1] “We found out about it [foreign RW treatment] in either 2018 or 2019, I am not sure.” A statement made by Mr. Gilbert Liška, the mayor of the municipality Veľké Kostoľany in the investigative videoreportage broadcasted on 15.06.2020 (part of “Reportéri RTVS” series) available at: https://www.rtvs.sk/novinky/zaujimavosti/227377/budeme-na-slovensku-spalovat-este-viac-odpadu (time 03:55-04:03)

[2] See, e.g., a statement of selected municipalities (in Slovak) available at https://www.jaslovske-bohunice.sk/evt_file.php?file=26988&original=stanovisko_obci.pdf and resolutions no. 2/28.10.2019, 3/28.10.2019 and 4/28.10.2019 of the Council of the Association of the municipalities in the region of the Bohunice NPP

[3] https://www.nuclear-transparency-watch.eu/activities/radioactive-waste-management/slovak-parliament-approved-a-bill-to-ban-future-contracts-for-incineration-of-foreign-radioactive-waste-according-to-the-slovak-ntw-members-some-concerns-still-remain.html

[4] During the period January 2021 – October 2021 94.78 and 37.81 tons of foreign and Slovak RW, respectively, were incinerated. i.e. the foreign RW share at incineration was 71.49% in this period.

[5] See, e.g., the statement of Mr. Gilbert Liška, mayor of the municipality Veľké Kostoľany, “We found out about it [foreign RW treatment] in either 2018 or 2019, I am not sure” made in the investigative videoreportage broadcasted on 15.06.2020 (part of “Reportéri RTVS” series) available at https://www.rtvs.sk/novinky/zaujimavosti/227377/budeme-na-slovensku-spalovat-este-viac-odpadu (time 03:55-04:03) and a statement of mayors of the affected municipalities dated 15 October 2018 demanding list of permits for incineration of foreign RW at RW TCT issued by the NRA SR and categorically refusing the foreign RW incineration (see p. 5-6 of the ruling no. 2764/2019-1.7/zg-R available (in Slovak) at: https://www.enviroportal.sk/eia/dokument/287520).

[6] See p. 90 of the English version of the EIS available at https://www.enviroportal.sk/eia/dokument/326075 or p. 86 of the Slovak version available at https://www.enviroportal.sk/eia/dokument/323308

[7] more precisely (according to a statement of JAVYS dated 17.12.2018): 50% increase in production of RW from NPP decommissioning combined with the start of production of combustible RW from operation of (to be commissioned) NPP Mochovce blocks 3 and 4 from 2020 onwards, i.e. 50% increase in the number of operated reactor blocks in Slovakia – from 4 to 6. However, the reactor blocks Mochovce 3 and 4 have not been commissioned yet.

[8] See p. 76 of the English version of the EIS available at https://www.enviroportal.sk/eia/dokument/326075

[9] Since the reactor blocks Mochovce 3 and 4 have not been commissioned yet, the missing contribution to increase in production of RW from NPP operation due to these blocks, originally expected by JAVYS in 2018, is not addressed here.

[10] The NRA SR responded to the request of information by the letter no. 3921/2020 dated 19.05.2020

[11] See https://www.rtvs.sk/novinky/zaujimavosti/227377/budeme-na-slovensku-spalovat-este-viac-odpadu at 11:22-12:50

[12] E.g., (1) news article dated 12.08.2020 available at https://www.aktuality.sk/clanok/813522/stali-sa-zo-slovakov-pokusne-mysi-olano-prudko-otocilo/ (translated from Slovak): “Sceptics are convinced that JAVYS needs the new incineration plant, because the sludges from Italy cannot be incinerated at the old one. Even people who have been employed in the nuclear energy sector for years have no doubts about it.”; (2) statement of the mayor of Veľké Kostoľany (one of the 9 affected municipalities) in the investigative videoreportage broadcasted on 15.06.2020 (part of “Reportéri RTVS” series) available at https://www.rtvs.sk/novinky/zaujimavosti/227377/budeme-na-slovensku-spalovat-este-viac-odpadu (time 04:27-04:46): “We suppose that the new incineration plant is being purpose-built, since the RW imported from Italy cannot be incinerated at the old one”; (3) official statement of the town Piešťany dated 28.04.2020: “At the time of signing the contract, it became apparent that treatment of this type of RW at the old incineration plant would be very difficult.”

[13] see NRA SR ruling no. 164/2021 P dated 24 May 2021, p. 20

[14] https://www.nuclear-transparency-watch.eu/activities/radioactive-waste-management/slovak-parliament-approved-a-bill-to-ban-future-contracts-for-incineration-of-foreign-radioactive-waste-according-to-the-slovak-ntw-members-some-concerns-still-remain.html

[15] See p. 49 of the English version of the EIS available at https://www.enviroportal.sk/eia/dokument/326075

By Jan Haverkamp (Greenpeace, WISE)

From 1996, the uranium enrichment facilities URENCO Almelo (Netherlands) and URENCO Gronau (Germany) regularly sent shipments of depleted uranium (DU) in the form of UF6 (uranium hexafluoride) to TENEX, later TVEL, in Russia, where this was stored in the open air in Seversk in the Krasnoyarsk region. Protests in Europe then halted these transports in 2009. TVEL is since 2007 a subsidiary of the Russian nuclear giant Rosatom. URENCO carries out enrichment for nuclear fuel production from natural uranium to low-enriched uranium for clients all over the world and has facilities in the Netherlands, Germany and the UK.

In 2019 and 2020, these transports were resumed from the enrichment facility of URENCO Gronau and URENCO UK in Capenhurst.

URENCO Almelo currently has a permit for export, but does not use it. Its DU is sent to France for conversion into stable U3O8 (depleted tri-uranium-octo-oxide or uranium oxide), which is returned to the Netherlands and handed over to the waste management organisation COVRA for interim storage in the VOG facility, awaiting final disposal after 2100.

The claim is that the DU is sent to TENEX, later TVEL, for re-enrichment to natural level and reuse of the resulting double depleted uranium (DDU). Rosatom furthermore claims[2] that DDU and DU are used industrially and that the UF6 also delivers fluorine for reuse purposes. It furthermore, describes in detail how it wants to convert its UF6 stockpile into uranium oxide for waste treatment before 2057.

Our conclusion is that this form of TENORM (technically enhanced naturally occurring radioactive material) should be considered in principle as a waste material, for which full transparency should be assured over its complete chain of management, also when a limited amount of the material may be used as resource. Research on optimization of the management pathways should be part of European research programmes like EURAD.

Our central observations are:

There is no transparency about the pathways of management of the DU exported by URENCO to Russia. There are claims of reuse on the Russian side,[3] but there are no clear descriptions of streams and involved amounts.

The Euratom radioactive waste directive defines radioactive waste as: “radioactive material in gaseous, liquid or solid form for which no further use is foreseen or considered by the Member State or by a legal or natural person whose decision is accepted by the Member State, and which is regulated as radioactive waste by a competent regulatory authority under the legislative and regulatory framework of the Member State;” (art. 3(7) 2011/70/EURATOM).

Article 4(2) of the directive states: “Where radioactive waste or spent fuel is shipped for processing or reprocessing to a Member State or a third country, the ultimate responsibility for the safe and responsible disposal of those materials, including any waste as a by-product, shall remain with the Member State or third country from which the radioactive material was shipped”.

Article 4(4) of the directive explains in more detail: “Radioactive waste shall be disposed of in the Member State in which it was generated, unless at the time of shipment an agreement, taking into account the criteria established by the Commission in accordance with Article 16(2) of Directive 2006/117/Euratom, has entered into force between the Member State concerned and another Member State or a third country to use a disposal facility in one of them.

Prior to a shipment to a third country, the exporting Member State shall inform the Commission of the content of any such agreement and take reasonable measures to be assured that:

(a) the country of destination has concluded an agreement with the Community covering spent fuel and radioactive waste management or is a party to the Joint Convention on the Safety of Spent Fuel Management and on the Safety of Radioactive Waste Management (‘the Joint Convention’);

(b) the country of destination has radioactive waste management and disposal programmes with objectives representing a high level of safety equivalent to those established by this Directive; and

(c) the disposal facility in the country of destination is authorised for the radioactive waste to be shipped, is operating prior to the shipment, and is managed in accordance with the requirements set down in the radioactive waste management and disposal programme of that country of destination.”

Furthermore, the Euratom directive obliges in art. 10 transparency concerning radioactive waste.

In Russian law, the definition of radioactive waste is “materials and substances not subject to further use, and equipment, articles (including spent ionizing radiation sources), in which the content of radionuclides exceeds the levels established in accordance with the criteria defined by the Government of the Russian Federation” (clause 8, article 3).[4] This is a much more shady definition, whereby the issue of responsibilities for waste material and waste as by-product are not defined. It may therefore well be that where there is responsibility for exported DU for the state of origin under 2011/70/Euratom, there is none under Russian law.

In the current set-up, ownership of this TENORM is transferred from URENCO to TVEL / Rosatom. Nevertheless, 2011/70/EURATOM stipulates that “the ultimate responsibility for the safe and responsible disposal of those materials, including any waste as a by-product, shall remain with the Member State or third country from which the radioactive material was shipped”. Logically, because URENCO Gronau does not reuse this material, for URENCO Gronau and Germany, this depleted uranium in the form of UF6 is a waste material for which it has ultimate responsibility – also when others claim (but not prove in the form of accountable and accounted for pathways) use as resource. After all, ‘ultimate responsibility’ when the material is (partially) not reused in any way but ends de facto as waste, can never be shed. This has several consequences:

Russia currently holds more than 1 million tonnes of DU in the form of UF6, around half of the world’s stockpile (Nikitin, 2020). It is unclear how much DU is held in stabilised form (in Russia, mainly DU3O8 – depleted tri-uranium-octo-oxide). Rosatom is planning to convert its complete stockpile of UF6 to DU3O8 before 2057. Re-enrichment after that date would require re-conversion into UF6.

To determine whether the to Russia exported DU may be considered to be a resource (in that case falling out of the scope of the Euratom radioactive waste directive), it is important to establish how much of the material is indeed reused for other purposes, which waste by-products are produced and which part remains for how long in storage without being reused.

Besides the earlier mentioned publication from Bellona / Rosatom, there is no public information available about this, nor any publicly available formal plans from TVEL / Rosatom.

According to Nikitin (2020), under Russian law, the material is seen as a “strategic reserve for the existing nuclear power industry” because of the possibility of re-enriching the material or use in fast breeder reactors.

From different sources, the following potential uses of DU can be found:

Nikitin (2020) puts a large emphasis on this. This is only possible when the uranium in the UF6 is stabilised in the form of uranium-oxides and the fluorine is extracted. The resulting (radioactive) uranium would then only be further useful in metallic form (weapons, balancing, other) and breeder reactors, but not for re-enrichment. Given the fact there is no market lack of fluorine, it is highly unlikely that UF6 for that reason would be kept as “strategic reserve” and hence justify labelling the DU as resource. Basically: declaring UF6 a resource because of the need for toothpaste is nonsense.

Given the limited availability of natural uranium in commercially viable extractable ores, re-enrichment of DU could squeeze out some more uranium for use in the nuclear fuel chain. Officially, re-enrichment is listed as justification for the export of DU by URENCO, and URENCO receives natural uranium back in return for the delivered DU.[5] It is unclear, however, whether this is indeed re-enriched DU or whether this is an equivalent of non-enriched natural uranium. Given the extremely energy intensive nature of enrichment, it is for cost reasons likely to be the latter.

When typical 0,2 – 0,25% DU from the enrichment facility of URENCO is re-enriched by TVEL to a level of 0,72%, 1 ton of depleted uranium yields around 0,25 tons of enriched uranium (natural level) and 0,75 tons of double-depleted uranium.[6] This means that ¾ of the exported DU will remain in Russia in the form of double-depleted UF6, whilst maximally ¼ can be reused again by URENCO as natural level uranium for further enrichment purposes. URENCO then, in turn, delivers from these 0,03 tons of enriched uranium (nuclear fuel level) and another 0,22 tons of DU, which could yield another 0,06 ton of natural uranium and 0.007 ton of enriched uranium, etc. After many cycles, re-enrichment of DU could yield in total around 4% of the initial DU as fuel for nuclear power. 96% remains behind as double depleted uranium.

Rosatom has declared on several occasions that the DU is to be used as plutonium breeding resource for its breeder reactors. It is currently operating two fast breeder reactors in Beloyarsk. In its Belona paper, it states that the DU is to function as a reserve for the next millennia for its ‘” fast” energy industry[7]. However, Rosatom already has an enormous stockpile of DU from its own sources, sufficient for covering many centuries of use in the theoretical case it would decide to continue to expand this extremely expensive way of electricity generation. For all substances that currently would fall under the definition of waste, one can dream up some kind of reuse in millennia from now, but they remain waste. Normally spoken, when a substance cannot be used within one generation – be it either because of lack of technology to reuse it or because of abundance – it is usually considered waste. Substances like paper, aluminium or steel have a reuse cycle within several years after being discarded. For that reason, fictional reuse in millennia from now cannot be used as an argument. As soon as next generations will have to take care of the management of material with toxic, radiotoxic or otherwise problematic properties, this material should be considered waste that is handed over to those next generations. Next to that, given the fact that fast breeder technology has proven so far to be an extremely expensive and risky way to generate electricity (accident risk, proliferation risk), there is a very realistic chance that nothing or only a minute part of Rosatom’s current stockpile of DU would indeed ever be used in fast breeder reactors.