Part 1: Do Bulgarian Citizens Know What to Do in the Event of a Nuclear Accident or Attack?

/Research in the Kozloduy NPP 30-kilometer zone /

Dr. Petar Kardzhilov

Abstract

Radiation protection and emergency preparedness and response are the two topics directly relevant to the health and life of citizens in one of the three main thematic circles for expert analysis and synthesis at the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) – Nuclear Safety and Security. Through research in populated areas in the 30 km zone around the Kozloduy nuclear power plant (NPP), based on the Extended Parallel Process Model, we come to the conclusion that there is no well-organized informational and educational activity on these two topics in Bulgaria.

An expert and responsible organisation of public communication on the risks and crises related to the increase of radioactivity in the environment, with the participation of all institutions, media and public groups, becomes even more relevant and necessary in the context of the new regional reality after the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian war.

Key words: risk communication, radiation protection, emergency preparedness and response, perceived threat, perceived efficacy, nuclear power plant (NPP), Russo-Ukrainian war.

After the start of the war in Ukraine, Russian troops took over the Chernobyl nuclear power plant and Europe’s largest nuclear power plant, Zaporozhye, firing at both, and a fire broke out in the latter. On several occasions, the Russian President and others at the top of the Kremlin have threatened Europe and the world with nuclear weapons. After the successive attacks on August 5 and 6, the Ukrainian nuclear regulator Energoatom reported serious damage with the forced shutdown of one of the units and the risk of leakage of hydrogen and radioactive substances at the Zaporozhye plant. The leaders of the IAEA, the EU and the UN condemned these events and called on the Kremlin authorities to allow a group of international experts to visit the NPP. In this context, the question arose for Bulgaria, a country very close to Ukraine and also operating its own nuclear power plant, whether the inhabitants of this country could protect themselves in a crisis situation with high radioactivity dangerous to health and life. Today, after the shutdown of all reactors in Zaporozhye NPP, the threat of attacks on the nuclear power plant has decreased, but Putin’s threats to use nuclear weapons have increased. Despite all these challenges, the attention of politicians and medias to these threats for Bulgaria is almost absent.

The study on preparedness and response to increased radioactivity in the context of the Russo-Ukrainian war is supported by the President of the Foundation for Environment and Agriculture, Albena Simeonova, with the help of the Ministry of Environment and Water, Minister Borislav Sandov, together with the Municipality of Kozloduy, the State Enterprise “Radioactive Waste”, the Municipality of Oryahovo, the Municipality of Mizia, the villages of Glozhene, Kharlets and Butan. It is conducted by myself, as a specialist in risk and crisis communication, following the model of American scientists in the field of risk communication, on 12 and 13 April in the towns of Kozloduy, Oryahovo, Mizia and the villages of Glozhene, Kharlets and Butan – all located in the 30-kilometer critical emergency planning zone around the Kozloduy NPP.

Scientific framework

The survey is not just a sociological or journalistic poll to capture attitudes and trends. It has a concrete practical and detailed scientific framework based on one of the most trans-disciplinary and complex areas of human knowledge – risk and crisis management. Risk and crisis communication is an integral part of risk and crisis management, which also carries trans-disciplinarity as its main characteristic and is studied in the developed countries as two separate academic disciplines – risk communication and crisis communication. The model in which the study was conducted is relevant to both disciplines, as it provides insights into how people perceive given risks, as well as how they react if those same risks manifested themselves as crises threatening their lives and health.

Human experience so far shows that increased radioactivity, in the event of a major accident in a nuclear power plant, or in the event of deliberate acts of terrorism or war, can create extremely serious threats to the health and life of the population and the state of the environment for decades to come.

But what should ideally be done? It makes sense to look for precisely the ideal option, because we are talking about a risk of loss of many lives and of great suffering for many people.

In order to react adequately in the event that these risks manifest themselves in the form of crises, and to minimise the negative consequences for people and nature, at the level of national and local institutions, the intervention of professional risk and crisis communicators is necessary.

They should fulfill the following tasks:

- Publicly formulate the risk variants and familiarise the public with the different possibilities of reaching a situation of dangerously high radioactivity in specific localities; inform the risk bearers of all possible negative consequences of such crisis situations.

- Periodically provide the public with comprehensive information on all possible actions and measures to protect life and health, with the help of all institutions and organisations related to these risks, and using all necessary communication channels and formats.

- To convince the public of the safety and effectiveness of the protective measures proposed by scientists and experts, and to assure people of their own ability to adopt the behavior recommended by the institutions.

The results of the study based on the model of the extended parallel process in the city of Kozloduy and neighboring settlements in mid-April show that in our country the implementation of these tasks has never started as a complete process, with the exception of isolated campaign activities, highly limited in terms of time, periodicity, expert involvement and scope.

Research model

The Extended Parallel Process Model, created by Prof. Kim Witt of the University of Michigan, examines the extent to which people perceive a given risk as a real danger to themselves – perceived threat (to health and life), as well as the extent to which they feel safe and prepared to react adequately if the same risk manifests itself as a crisis with a direct danger to them – perceived efficacy (of the defensive response).

Perceived threat consists of two parallel human perceptions – of vulnerability and of severity. Perceived vulnerability refers to the degree to which someone believes that the risk is likely to manifest as a crisis, and perceived severity relates to the degree of severity of the consequences of the crisis that someone perceives. Perceived efficacy includes a person’s perceptions of the efficacy of the generally accepted response and of their personal efficacy. Response efficacy concerns the degree to which one perceives the safety and effectiveness of the recommended behavior, whereas personal efficacy depends on the extent to which one perceives that he/she has the necessary skills and resources to engage in the recommended behavior. This is how two pairs of parallel processes are obtained, which take place in our consciousness when we are faced with risks, crises and emergency situations.

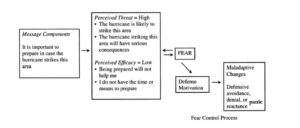

Figure 1: The extended parallel process model (Witte, 1992)

There are three psychological reactions depending on the impact of information about the danger and the corresponding individual level of threat perception and efficacy:

1) when the perceived threat (vulnerability and severity) is low, an absence of reaction most often follows: a change in behavior and, accordingly, actions do not occur;

2) when perceived threat is high and perceived efficacy is low, several variants of situationally inappropriate behavior follow, summarized by the concept of fear control;

3) the adequate reaction for the protection and self-defense of citizens is realized at high levels of both the perceived threat and the perceived efficacy, which Prof. Witt defines as danger control.

Peculiarities of the study

The survey card is based on the model of the parallel process and includes a total of 13 questions, 10 closed (with indicating one of several answers) and 3 open questions (with writing one answer). One part of them relates to the perceived threat (vulnerability and seriousness), the other part – to the perceived efficacy (reaction and personal). The third part is additional questions that help form a conclusion about the most likely psychological reaction that will occur in society in the event of a real crisis with increased radioactivity.

It is important to note that almost all of those who accepted to fill out the survey were women – 141 women and only 30 men. On the one hand, the reason for this is that in general more women work in these institutions. On the other hand, in the field, there is a reluctance among some men to participate in the survey on the topic of radiation protection. These reactions among men should be studied separately, as they would create additional complications in the process of radiation protection preparation and response.

Presentation of the study, presented at an international online conference on the security of European nuclear power plants in the context of the war in Ukraine can be seen here: https://www.slideshare.net/PetarKardjilov/eprnppwar052022ppt

The perceived threat of high radioactivity events

Here there are four questions, three of which are variants of perceived vulnerability to the different nature of the event, and the fourth one is to the perceived severity of such an event. To the first question: “How likely is it, in your opinion, for a major accident at the Kozloduy NPP to result in high levels of radioactivity in the area where you live?”, 7.6% of respondents answered “completely impossible”. 35.4% with “rather impossible”, 20% with “50:50%” answer, 9.4% with “rather possible”, 27% with “completely possible”. Although by a little – with a total of 56.4%, three groups perceiving this risk as real prevail, one group accepts it as potential, but far from the possibility of its occurrence – 35.4% and only 7.6% perceive it as unreal. The perception of the risk of a major nuclear plant accident as real by most respondents indicates that their perception of vulnerability is rather high. This data enters as an asset in the overall level of perceived threat, which, if it remains high after adding the data of the perceived severity of the event, will reduce the probability of achieving the first of the three possible mental reactions according to the model – no reaction.

Perceived vulnerability is even more categorical in the answers to the question: “In your opinion, how likely is it that a serious accident at a nuclear power plant would occur in a war near Bulgaria, affecting Bulgaria as well?”. Here 10.5% responded with “completely impossible”, 18.7% with “rather impossible”, and 8.3% with “no more than before the war”. 28.6% define such an event as “rather possible”, and 33.3% as “completely possible”. A total of 61.9% (marking the last two answers) perceive this different from the previous risk as real. The data on the perception of this different type of risk in the new military context as real by most respondents further reinforces the indicators of perceived vulnerability in the context of a commonly defined event of high radioactivity in the environment.

The perceived vulnerability is most strongly expressed in the answers to the third question about vulnerability – the possibility of a nuclear attack near the country: “In your opinion, how possible is it that a military nuclear attack could happen near Bulgaria that would affect our country and part of the Bulgarian citizens?”. Only 12.8% think that such a situation is “completely impossible” and only 3.5% that it is “rather impossible”. According to 27% it is likely “50:50%”, for 29.2% it is “rather possible”, and for 26.3% it is “completely possible”. This is already a third type of risk, again in the current military context, which is perceived as real by even more respondents, which is evident from the last three answers, the sum of which is 82.5%. From the data in the answers to these three questions, we can assume that we have an undoubtedly firm perception of high vulnerability in all three different types of risks of a crisis situation with high radioactivity – an accident at the Bulgarian NPP, an incident/attack at a NPP close to the country and an attack with nuclear weapon near the country.

In the perceived threat asset, parallel to perceived vulnerability is the perceived severity of the emergency event for which there is a risk. This parallel psychological process of the perceived threat is particularly vividly defined in the study from the city of Kozloduy and the region. To the question: “What do you think would be the consequences for health and the environment if a major accident occurred at the Kozloduy NPP, or at another NPP near Bulgaria, or in the event of a military nuclear attack nearby – in all three cases with high radioactivity in the atmosphere and environment?”, none of the respondents answered “insignificant”, only 5% answered “significant but repairable”, 59% answered “very serious and long-lasting” and 34% marked the answer “very serious and irreparable”. The sum of those who indicated the three answers to the question about the perceived severity is as much as 98%, which undoubtedly means that the respondents are aware of the severe consequences for their health, life and well-being that could occur as a result of an accident or attack with high radioactivity.

Following the data from the responses to the three vulnerability questions, the data from the severity question simply “concrete” a definite conclusion about a high level of the first of the two main parallel processes in Witt’s model – perceived threat. The overall conclusion from the responses to the perceived threat questions is that it has sufficiently high values that the first of the three possible psychological reactions according to the model – the absence of a reaction – will not take place in the case of an emergency event with high radioactivity in the studied area. However, which of the other two behaviors will respondents have according to the other two forms of psychological response? Whether they will take one of the harming pathways of fear control or reach an adequate rescue response along the path of danger control, however, depends on the data for the second parallel process — the perceived efficacy.

Perceived efficacy in high-radioactivity events

While the threat of an event with high radioactivity is perceived by the respondents in a positive way, i.e. primarily as a real or potential risk with very serious consequences for health and the environment, the efficacy of an adequate response to such an event is perceived by them categorically in a negative way – as unknown, impossible, ineffective or unattainable. Similar to perceived threat, we measure perceived efficacy factors with four other questions – three on response efficacy and one on personal efficacy. I recall here that response efficacy concerns the degree to which one perceives the certainty and effectiveness of one’s recommended behavior, whereas personal efficacy depends on the extent to which one perceives that one has the necessary skills and resources to engage in the recommended behavior.

The first question is open: “In the event of an accident at a nuclear power plant or a nuclear attack with the presence of high radioactivity in the atmosphere near your place of residence, do you know what protective measures you should take yourself and what when ordered by the institutions?”, as after this question in the survey card, two lines are left to clarify the two types of protection measures. 39% answered “no”; 31% answered only “yes” but did not explain; 9% answer with “yes” and write measures that are, however, incorrect; 8.6 answer with “yes” but record only some and do not distinguish between the two types of measures; 2.5% write that the measures are useless, and 9.9% do not answer the question.

The conclusion from the answers to this open-ended question is that none of the respondents is sufficiently aware of what response would be most adequate when hearing signal sirens with a message of radiation danger. I will consider in detail the issue of radiation protection measures and actions related to preparation and response to an incident (or attack) with increased radioactivity in the second part of the article. There we will also dwell on specific answers of the respondents received in the survey. We will note here in general that these measures and actions are very rarely communicated, are difficult to find online and offline, are unclear, contain contradictions and cause many questions. However, there are clearly distinguishable measures and actions that citizens should take on their own, as well as those that they should only take when instructed by state institutions through the media. For example, among the first type of measures are maintaining a package for emergency situations in homes, insulating doors and windows, among the second – taking potassium iodide tablets and evacuation.

To the next question about the response efficacy: “In your opinion, are the protection measures recommended by the institutions safe and effective in the event of a major accident at the nuclear power plant?”, only 4% noted the answer “completely certain”, 18% noted “more almost certain”, 34% answered with “I can’t judge”, 16% with “rather uncertain”, 9% indicated “completely uncertain”, 19% noted the answer “I don’t know the measures”. This second question of reaction efficiency both complements the first and serves as a check on it. Those who marked the first two answers “completely certain” and “rather certain” are a total of 22%. However, taking into account all the answers to the first question, it is clear that these respondents have the delusion that they know the measures, but in reality this is not the case. The total of 78% of all other responses indicates a clear preponderance of low perceived. This multiple expresses firm uncertainty about the response efficacy.

The third question about the response efficacy is “Do you trust the government institutions to do everything necessary for your safety and that of your family in the event of an incident with increased radioactivity?”. Here, only 8.9% answered with “I trust them completely”, 29.2% with “I trust them, but I have doubts”, 19% with “I can’t answer”, 24.7% with “I don’t trust them” and 18.2% with “I don’t trust them at all”. Subject to this response efficacy question are the entities with (in theory) the most resources and capacity to act to protect society in a crisis event of this magnitude. If here too there is no feeling of stability and security among the respondents, then, together with the data from the answers to the other two questions, we come to the conclusion that the perceptions of the response efficiency are extremely low. Indeed, such a feeling is hardly present: it is present in only 8.9% against uncertainty and mistrust in the majority of 91.1%.

Fourth is the question of personal efficacy: “Do you have the necessary skills and resources to take the individual and general measures recommended by the institutions, in the event of a major NPP accident with high-radioactivity near where you live?”. Only 5.8% answered with “yes”, 17% with “rather yes”, 32.7% with “rather no”, 19.5 with “no” and 25% with “I don’t know what the necessary skills and resources are”.

It is unacceptable, under the standards set by the IAEA[1], which are mandatory for all countries with nuclear power plants, that in the 30-kilometer emergency planning zone, a quarter of the 171 citizens asked to answer that they did not know what skills and resources they need to protect themselves in case of a high-radioactivity crisis and half of them to indicate that they do not have or rather do not have any. Moreover, we speak about respondents working in institutions that should lead the response actions in such a crisis and radiation protection – schools, hospital, municipal administration.

With the data from the responses to the personal efficacy question added to that from the responses to the three response efficacy questions, we conclude that there is very low perceived efficacy in the event of a high-radioactivity crisis event. This is how we arrive at the answer to the equation according to the Extended parallel process model:

high perceived threat + low perceived efficacy = fear control

Additional questions on perceived threat and efficacy

We use several additional questions with the following tasks:

1) to obtain more detailed information about the current factual situation with the provision of information and training to local communities;

2) to check the propensity of citizens to search and remember information related to current risks on the subject in the context of the war in Ukraine;

3) to explore their willingness to seek a higher level of protection in the event of a high-radioactivity crisis in the new situation of close war;

4) to specify the conclusions we reach from the data from the answers to the previous eight questions, according to the of the Extended parallel process model used in the study.

The first three questions of the survey compile data on perceived threat in today’s current situation of nuclear power plants seized by military force and threats of nuclear attack. In accordance with the current information about the new risks in the context of the war, we ask in an open question: “Do you know which nuclear power plants in Ukraine were captured by the Russian army?”. Only 7% of respondents gave the correct answer “Zaporozhie NPP” and Chernobyl NPP”, 18% indicated Zaporozhye NPP, 20.5% – Chernobyl NPP, 45.7% answered “no”, 2, 3% indicate the non-existent “Mariupol NPP”, 6.5% didn’t answer.

To the next additional question about the perceived threat: “Can Bulgaria protect its nuclear power plant in the event of a military attack?”, 32.7% answered “yes”, 51.6% “no”, 9.3% noted ” I don’t know” and 6.4% do not give an answer.

To the third additional question about the perceived threat: “Should the European Union build a common system to protect the nuclear power plants of the member countries that operate them?”, 87.7% noted the answer “yes”, only 5.8% answered with ” no”, 6.5% didn’t answer.

Data from the respondents’ responses indicate that the level of concern at the possibility of vulnerability in the new context of close warfare is high. Half of the respondents remembered information related to the capture of the Ukrainian nuclear power plants by the Russian army, although both nuclear power plants were captured five and six weeks before the date of filling out the survey. The overwhelming responses to the other two additional questions on perceived threat show that respondents do not believe in the power of the state to protect our nuclear power plant and wish to take action to protect it at European level. The data from all three additional questions reinforce those from the main four questions about a highly perceived threat of a possible crisis with hazardous radioactivity in the new reality of a hot positional war close to Bulgaria.

Answers to the additional two questions on perceived efficacy also strongly indicate its particularly low, even tending to zero, level, confirming the result of the main four efficacy questions. Here, the clearest absence of a strategy and systematic communication (informational and educational) approach in radiation protection, preparedness and response to an emergency situation with increased radioactivity is found.

To one of the two additional questions related to perceived efficiency: “How often do you receive reminder information from the institutions regarding the necessary response and measures in the event of a major accident at the Kozloduy NPP with high radioactivity in the environment?”, as many as 63% of respondents answered with “I don’t remember receiving such information”. Another 7% answered “more than 5 years ago”, 2.3% highlighted “5 years ago”, and another 2.3% marked “3 years ago”, 1.6% answered “once every two years”, 12.3% – “once a year” and 8% – “twice a year”.

The other additional question about the perceived effectiveness is open: “Has a response exercise in case of a major accident at the Kozloduy NPP ever been organized in your locality? (If the answer is yes, please write when it was and what you remember from the teaching.)”. 59.4% answered “no”, 14% wrote that they did not remember participating in such an exercise, 12.4% did not answer, 5.3% answered “yes” but did not explain, 6% answered ” yes”, writing only the date and only 2.9% answered with “yes” and indicated a specific date and memory.

Conclusions of the study

Given the results of the answers to the last two additional questions, which are directly related to response efficacy and personal efficacy, it is very important to note again that almost all of the 171 citizens of various age groups who participated in the survey in the 30 km emergency planning zone around the Kozloduy NPP, reside mostly in institutions that should have leading roles in the public response to a crisis with high radioactivity – six municipalities, three schools, one hospital, as well as two hotels in the city of Kozloduy. In this situation, there is no reason to assume that the preparation for radiation civil protection in other cities and regions of Bulgaria outside this 30-kilometer zone would be at a better and adequate level. In this regard, we must bear in mind that, in addition to our nuclear power plant, the now captured Ukrainian NPP “Zaporozhie”, only 65 km from Silistra, the Romanian NPP “Black Water” is operating. We must not forget the Turkish Prime Minister Erdogan’s intention to build a nuclear power plant next to Ineada, just 10 km from Rezovo.

As leading conclusions in the research based on the Extended parallel process model, on the one hand, we see the trend of:

- Clearly expressed perception of the threat in the risks of an event with increased radioactivity, with sufficiently high attention of the respondents to the two parallel factors of the threat – the vulnerability and the severity of such an event.

- On the other hand, the response data for the other main parallel process – perceived efficacy (with its two parallel factors – reaction efficacy and personal efficacy) – show very low, in some places almost zero values, expressed by ambiguity, confusion, ignorance and uncertainty in the answers of the surveyed citizens regarding the principles of radiation protection and the response to a crisis with dangerously high radioactivity in the environment. Thus, the analysis of the data reaches the most significant conclusion for the study, that if an emergency situation occurs with dangerously high radioactivity in the environment:

- Bulgarian society will mainly realize the second psychological reaction from Witt’s model – fear control. Namely, when the subject perceives a high threat but does not perceive a feasible option to limit it, he/she tries to control his/her fear instead of the actual danger.

Fear control has several variants of crisis-inappropriate behavior. When it comes to a message that warns people about a crisis that is expected to occur soon, fear control is expressed in maladaptive changes such as defensive avoidance (e.g., ignoring the information), denial (e.g., refusing to believe that the risk is real) or resistance (eg rejecting the message as manipulative). However, when it comes directly to a crisis alert message (in this case, human-damaging radioactive substances released into the environment in an accident or intentionally through a military attack), citizens will react according to what they know and what they don’t know at the time of receiving the alert message. Then, the fear control will transform into uncontrolled fear, from which panic actions will follow, that in turn will lead to an exponential increase in the negative consequences of the crisis. Therefore, I add to Witt’s model the state of panic as a possible maladaptive change in behavior when a crisis has suddenly occurred.

Figure 2: EPPM High Threat Low Efficacy example – Fear Control

Awareness of protection measures is very low even in the populated areas in the 30-kilometer zone around the Kozloduy NPP. One of the rare materials on the subject, for example, is a leaflet uploaded to the page of the Main Directorate “Fire Safety and Protection of the Population” on the website of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, produced by the Kozloduy NPP, which contains some inaccuracies, ambiguities and raises questions that are not answered answered. There is an urgent need to update and refine information on preparedness and response to a high-radioactivity crisis by adequate specialists, as well as a program for its wide and periodic dissemination.

In the second part of the study, we will examine the factual situation with information about radiation protection in Bulgaria and the countries of the European Union. We will give specific guidelines for the necessary changes so that Bulgaria can build adequate planning for preparation and response to crises with the release of dangerously high radioactivity into the environment, as well as a communication strategy for informing and educating about the risks of such crises.

References

- Coombs, W. T. Choosing the right words: The development of guidelines for the selection of the “appropriate” crisis response strategies. – Management Communication Quarterly, pp. 474 –475, 1995.

- Heath, R., O’Hair, D. The Significance of Risk and Crisis Communication. In R.L Heath & H.D. O’Hair (Eds.). Handbook of Risk and Crisis Communication (pp. 5–29). – New York, NY: Routledge, 2009.

- IAEA. Preparedness and Response for a Nuclear or Radiological Emergency: IAEA Safety Standards for Protecting People and the Environment Series, No. GSR Part 7, 2015.

- Witte, K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Communication Monographs, 59, 329–349. 1992.

- Roberto, A., Goodall, C., Witte, K. Raising the Alarm and Calming Fears: Perceived Threat and Efficacy During Risk and Crisis. In R.L Heath & H.D. O’Hair (Eds.). Handbook of Risk and Crisis Communication (pp. 285 – 291). – New York, NY: Routledge, 2009.

[1] Preparedness and response for a nuclear or radiological emergency section on the IAEA website here: https://www.iaea.org/publications/10905/preparedness-and-response-for-a-nuclear-or-radiological-emergency

You must be logged in to post a comment.